Op-ed: Increased lithium demand for electric vehicle batteries comes with a price

07/13/2021 / By Ramon Tomey

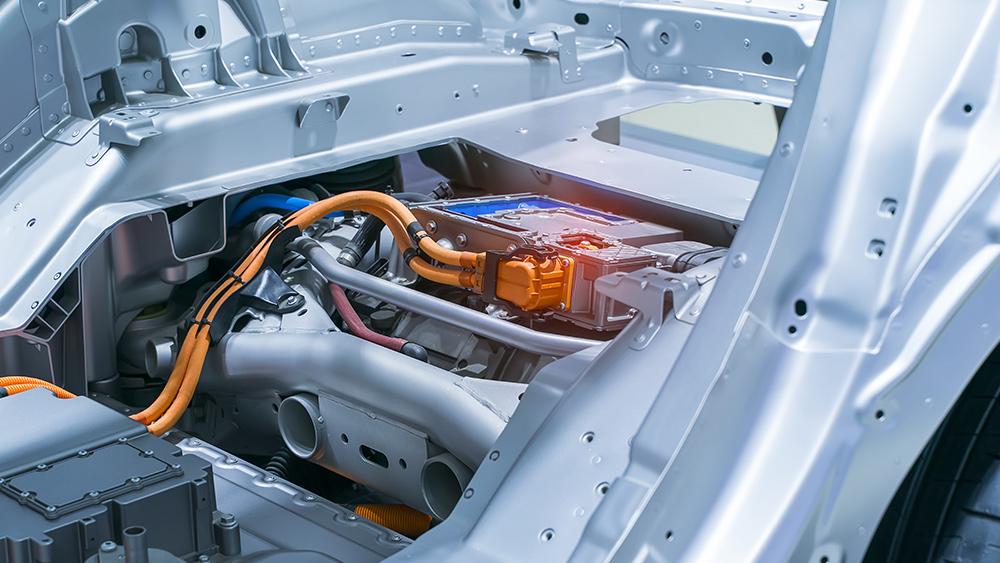

The recent push toward clean energy and transportation has driven up demand for electric vehicles and the batteries that power them. Lithium is an important element in the manufacture of electric vehicle batteries, and the Atacama salt flat in Chile holds most of the world’s lithium reserves. However, extracting this element from the salt flat comes with a huge price – as a professor has claimed.

Providence College professor Thea Riofrancos elaborated on the potential impact of lithium mining in Chile in a June 14 op-ed piece for The Guardian. She acknowledged the need to shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy in order to reduce carbon emissions. Lithium batteries hold a key role in this shift by powering electric vehicles and storing energy on renewable grids. But mining efforts for this element threaten surrounding communities and the environment.

Riofrancos cited a recent report by the International Energy Agency on so-called “critical minerals” for clean energy technologies. According to the report, meeting the climate targets set by the Paris Agreement would increase demand for these minerals. It also projected that by 2040, demand for lithium will be 42 times more than that for 2020. She then posited this question: “Does fighting the climate crisis mean sacrificing communities and ecosystems?”

The professor also mentioned the process of extracting lithium in the Atacama salt flat. Brine is pumped to the surface and collected in evaporation ponds, resulting in lithium-rich concentrates. The process required large quantities of water – a luxury in the dry Chilean desert. Aside from lithium extraction, copper mining and processing have also undermined the South American country’s environment. Chile is the world’s top producer of copper.

The water-rich lithium extraction procedure has reduced the freshwater available to the indigenous communities living on the salt flat’s perimeter. It also disrupted the habitats of animal species such as Andean flamingoes (Phoenicoparrus andinus), she added.

Riofrancos wrote in her piece that waste from mining contaminates both waterways and soil. Once the minerals are extracted from the ground, mining companies tend to rake in huge profits. This comes at the expense of the poor communities near the depleted mines – who now have to live in a contaminated environment. “The communities who suffer the harms of extraction are frequently denied its benefits,” she remarked. (Related: Chile is sitting on a lithium goldmine, but locals say that exploiting it will come at a terrible environmental cost.)

There is a delicate balance between zero-emission technologies and protecting the environment

The professor noted in her piece that the transition to renewable energy is often understood as a war between fossil fuel-reliant energy companies and advocates of climate action. However, she noted that this conflict only reflects different visions of a low-carbon world – with multiple paths toward them.

The demand for critical minerals such as lithium also translated into geopolitical conflict. American and European policymakers have repeatedly talked about a “race” to secure the minerals required for green energy and stock up on domestic supplies. This idea of a “new cold war” with China, a rising power, also accompanied this rhetoric.

On the other hand, stakeholders affected by the race to secure critical minerals have pushed back. Environmental activists, indigenous communities and concerned residents have protested against what they consider as the “green-washing” of destructive mining.”

Riofrancos suggested three ways to alleviate the negative effect of lithium mining and meet emissions targets. First, transportation systems should be designed in such a way that they favor mass transit, cyclists and pedestrians. A system with individual electrical vehicles and landscapes dominated by highways and suburban sprawl uses up more resources and energy, she claimed.

Second, the demand for overall energy should be lowered. This would subsequently reduce the materials footprint of technologies and infrastructure connecting homes and offices to the larger grid.

Third, there should be a push toward materials recycling and recovery. Riofrancos said: “Not all demand for battery minerals must be sated with new mining.” She pointed out that recycling and recovering metals from spent batteries can suffice for obtaining lithium without the need to undertake environmentally destructive mining operations. Governments ought to invest in recycling infrastructure and mandate companies to use recycled materials, she added. (Related: Is it possible to recycle lithium ion batteries?)

The professor ultimately remarked: “Rather than an excuse to intensify mining, the accelerating climate crisis should be an impetus to transform the rapacious and environmentally harmful patterns of production and consumption that caused this crisis in the first place.”

Visit Pollution.news to read more about the negative effects of extracting lithium for batteries.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: Atacama Salt Flat, Chile, critical minerals, destructive mining, electric vehicles, EV batteries, lithium batteries, lithium mining, renewable energy, Thea Riofrancos, zero emissions

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 SCIENTIFIC NEWS